Profluence Defined

Or, how to keep your readers turning pages

If I had to make a guess, I’d say that the biggest game changer for the writers I work with happens when they begin to understand the concept of profluence. It’s something they’ve never heard of before but, once it’s explained, a light bulb goes off in a major way. If they roll up their sleeves and do the work of ensuring that each chapter earns its place by having profluence, their writing and story improve by a wide margin.

So, what exactly is this profluence I speak of?

Profluence Defined

Profluence is a fancy MFA term that comes from John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction—great craft text, if you haven’t read it. Here’s what Gardner says:

“By definition – and of aesthetic necessity – a story contains profluence, a requirement best satisfied by a sequence of causally related events, a sequence that can end in only one of two ways: in resolution … or in logical exhaustion” (53).

The key here is “a sequence of causally related events.” A happens and so B happens, which causes C to happen and so forth. More on causality later. It’s important. Like, really important.

According to Gardner, profluence is the “root interest of all conventional narrative” and you’re only doing this successfully as a writer if the reader is “intellectually and emotionally involved … [and] led by successive seemingly inevitable steps … to its relatively stable outcome” (55).

Translation? The reader wants to keep reading because their heart and brain is invested in what’s going to happen next.

In short, profluence occurs when the reader wants to keep reading because the writer has given them an opportunity to make predictions about what might happen next…and they keep reading because they want to see how things play out. It’s VERY satisfying for a reader to see if their predictions are correct. For many of us readers, this puzzling out is happening at a subconscious level. We’re, as Lisa Cron says, “wired for story” and so our brains are constantly taking in all the clues and information and trying to determine what will happen next. If you’re reading a thriller or mystery, then profluence is baked into the genre—many readers dig into those books precisely for the opportunity to solve the story. But, no matter what the genre, profluence is playing a starring role—it’s just too modest to take center stage the way plot and character do.

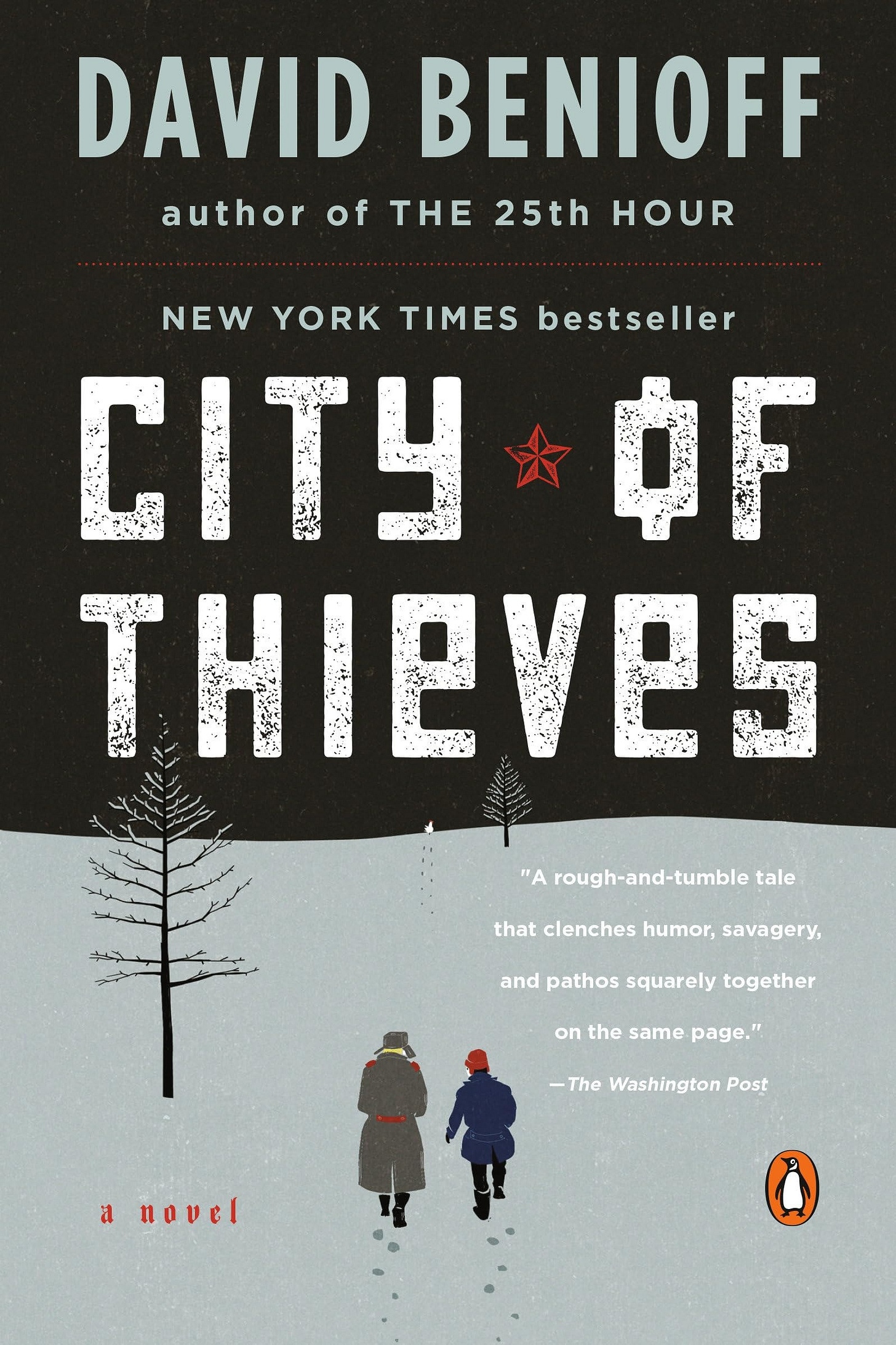

One of my favorite books—and one with theft of profluence that keeps on giving—is David Benioff’s City of Thieves. The premise is this: Two dudes are given a choice during the Nazis’ siege of Leningrad: be executed for crimes they committed or be pardoned if they can procure a dozen eggs for a big-shot Soviet military leader’s daughter’s wedding cake. We’re talking find a dozen fresh, unbroken and unfrozen eggs in a city where there is so little food that people are literally eating each other. Also, it’s the dead of winter. Also Nazis. Hello, profluence!

Here’s the last paragraph of the first chapter, which is when Lev, our protagonist, has been picked up by Soviet soldiers when he’s caught looting. They shove him in a car. This is bad. This is really bad:

“I decided I was still alive because they wanted to execute me in public, as a warning to other looters. A few minutes before, I had felt far more powerful than the dead pilot [whose dead body he’d been looting from]. Now, as we sped down the dark street, swerving to avoid bomb craters and sprays of rubble, he seemed to be smirking at me, his white lips a scar splitting his frozen face. We were going the same way.”

I mean, come on. How can you NOT keep reading? We’re dying to see what’s going to happen to Lev. It’s the top of the book—he’s gonna get out of this pickle somehow. But HOW?

This is an example of the cliffhanger kind of profluence, where you absolutely must turn the page because you want to see if The Dramatic Thing will happen. It’s the more typical kind of profleunce and a good place to start if you want to play around with the concept not he page and aren’t sure how.

Here’s an example of less obvious profluence, which happens throughout the short first chapter of Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower:

“I had my recurring dream last night. I guess I should have expected it. It comes to me when I struggle —when I twist on my own personal hook and try to pretend that nothing unusual is happening.”

Y’all, that is the first two sentences of a book filled to the absolute BRIM with profluence. As a reader, I’m invested—I feel for this character, who is clearly suffering (“my own personal hook”) in a world where “unusual” things are happening. Anything unusual has profluence because we get curious—what is going on here? What’s happening in her world?

At the end of the chapter, we learn that we’re in a future where there are far fewer city lights, that it’s much easier to see the stars now, that seeing the stars means there is no longer progress (according to some views) and that people can’t afford electricity, but they can afford the stars.

Why do we keep reading here? Where’s the profluence? Butler weaves it in throughout the chapter so that, by the end, we want to know more about this world where people in Los Angeles can’t afford electricity, where our protagonist is fighting against the realization that something unnamed and definitive and foreboding is coming to her and her community, that something is wrong, and she doesn’t yet want to see what it is. We’re making predictions about this future world—is it post-apocalyptic? Climate change? Another pandemic? We have to know, and we have to know because we already care about the protagonist. Her vulnerability in sharing her dream, her love of the stars, her stepmother’s grim acceptance of this sudden new upside down world where progress has been halted…Remember, Gardner talks about the reader needing to be “intellectually and emotionally involved” for profluence to occur.

Have you ever read a book that seems to have profluence—cliff-hangers, mysteries, etc.—but you don’t keep reading? You actually don’t care if your predictions are true, you don’t need the itch of curiosity scratched? That probably happened because you didn’t care about the protagonist. Books are only truly bingeable if the characters themselves are bingrable!

Is it profluence?

Here are a few ways profluence might show up in a chapter:

A chapter ending that ends on a question or some kind of mystery or uncertainty has profluence because this creates a context for us not knowing something we want to know.

A character either making a decision to do an action or deciding that it’s time to make a decision. One of the reason Sally Rooney is one of the only truly bingable literary writers of our day (IMHO) is because her characters are often having to make tough decisions that play into their larger issues as humans trying to human in this world. And we resonate with the banal complexity of that and we want to see what they would do…and is it what we would do?

Something dramatic happening—cliffhanger material, game changing actions (think the Red Wedding in Game of Thrones).

A character experiencing a major loss (Sirius dies! Dumbledore dies! Now what???).

An offer or opportunity that the character has to act on. (Helen Hoang’s The Kiss Quotient—so bingable!—is a great example of this).

A mystery of some kind—think Gone Girl. Where did she go? What happened? And what does Nick have to do with it?

A realization a character has about themselves that you, as the reader, know will influence future action and you’re curious about how that will play out. (For some reason, I just heard Cher in Clueless say, “I love Josh!”).

Bingeable Chapters and Profluence

Great chapters end with profluence!

If you’ve read my post on how to write a bingeable chapter, then you know that all bingeable chapters end with an objective (an acting term for a desire that the character has - it’s something they want and are going to do all kinds of interesting things to try and get). The reader wants to see the protagonist go for that thing, whether it’s to find an answer, kiss the girl, set the boundary, ditch school, find the killer. This also makes it easy for you as the writer, because it sets you up for your next chapter. Your objective at the end of chapter one can become your objective for the top of chapter two (another bingeable rule: all bingeable chapters are bookended by objectives).

You know you have profluence if you are certain your reader will want to keep turning the pages based on what happened in the last page or so. You can play this out longer, but our readers have much shorter attention spans than they used to, so ensuring that profleunce is there in the last page of the chapter (even if it shows up as a reminder of some kind) will keep the book in your reader’s hand.

One of the questions I love from the craft book Story Genius (Lisa Cron) is “And so….?” It’s a question you ask at the end of a chapter—and so….why should I carte? And so…this next things happens (this is a case of causality, which is ESSENTIAL for all good storytelling. George Saunders explains this best in his epically amazing craft book A Swim in a Pond in the Rain).

And so….? is a phrase you might think about using as you look back through your chapter endings in your manuscript. If there’s no clear “and so” from the protagonist, then you’re lacking profluence. Meaning, your chapter ended without any invitation to your proto for further action. Something happens in the chapter that, by the end of the chapter, should prompt a response. Her father is killed. And so….she resolves to find the murderer. Or: Her aunt tells her she can’t leave the house to see her secret boyfriend. And so….she decides to figure out how to disable the security system. (Presumably, the next chapter shows her doing these things).

Notice that profluence is inherently active. It’s an energy that gives your protagonist agency and keeps them from being a passive protagonist where things happen to them.

Obstacles

“Causality is to the writer what melody is to the songwriter.”

- George Saunders, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain

One of the reasons obstacles are a good bingeable writer’s bread and butter is that each obstacle creates profluence. It’s an unknown thrown into the mix and the reader wants to see how it plays out.

I recently had one of the writers I work with list all the obstacles in a chapter from Rebecca Yarrow’s Fourth Wing. I had her do the same for the cozy fantasy Legends and Lattes. The whole reason people read cozy fantasy is because the obstacles stress them the hell out and they just want to snuggle up to magic without the tension that usually goes with it. The lists were hilariously different—Fourth Wing was obstacle upon obstacle, each one compounding so that you can’t turn the pages fast enough. In contrast, there was maybe one obstacle in the chapter from Legends and it was very low stakes (the whole point of the genre—the author is doing their job, in this case). Note: my writer looked forward to reading both books. So, there was profluence in Legends and Lattes, but it looked very different than the more straightforward profluence of the high-stakes Fourth Wing. Keep in mind, too, that all of this subjective to a large extent - we might not agree on what makes us want to keep reading as individuals. However, when you break down books that are bingeable - ones you really can’t put down - you see that overt profluence plays a huge role.

Which leads me to….an assignment!

Your Homework Assignment

Choose either your current read or a past fave bingable read and start noting where there is profluence. You’re looking for the places where you as the reader are naturally making predictions or having good questions, like “Will they end up together?” or “Can she really stay alive in that spacesuit she just put duct tape all over?” You know it’s profleunce when you’re getting curious and you want the answer to the question. That answer doesn’t have to come in the next chapter—it might not happen until the end of the book, or series (re: Game of Thrones). You might also compare different styles of books to see how profluence works differently in them. Compare the profluence in Becky Chambers’s Monk and Robot books to that of Marissa Meyer’s Cinder. In my experience of these two sci-fi books, I couldn’t put one down (Cinder), but I felt very tenderhearted toward the other (Chambers). I don’t find Chambers bingeable, but I don’t need all my books to be bingable. I, do, however, need to have some curiosity which leads me to keep turning pages (profluence!). Those reasons can be quiet (will Dex figure out their existential crisis in A Psalm for the Wild-Built) or loud as hell (Will Cinder the cyborg and Prince Kai find a way to make it work…and will Cinder save the planet?)

Remember: Profluence is pleasurable! If it’s not fun, it’s not profluence.

Extra Credit: Are you ready to keep your readers up all night?

My on-demand course, Writing Bingeable Characters, is for you if you’re digging what you’ve read so far. There’s a super fun writing assignment that you build on throughout the course, loads of delicious worksheets to explore your personal binge factors, and tons of resources to support your craft, story, and writing practice.

For further investigations on profluence:

Check out my pal writer Ingrid Sundberg’s post on the concept.

Read this excerpt from Saunders on The Marginalian where he gets into the concept of causality.

And, once again, here’s my How To Write A Bingeable Chapter post.

I needed to find out about profluence and figured out it is what I already strive for. Helpful, good read.

If anyone is reading this post and wondering if they'd like to buy the course Writing Bingeable Characters, YOU DO!!! I bought it a few years ago and have revisted the entire course (and others from Heather!) MULTIPLE times. It is invaluable and I think about it ALL THE TIME while writing. Thank you Heather!!