Writing with Chronic Pain

...and some reflections on The Salt Path Controversy

The way we talk about illness and disability dictates what is possible for all people who are affected by it. The narrative odds are too often stacked against disabled people. There are two options that seem to be available: triumphal recovery or inspirational death.

Polly Atkin, Some of Us Just Fall

Camerados-

☠️ I’ve been wanting to write about chronic pain for a while and I think this will be a bit of a series, with this missive being the first of a few posts—you can let me know in the comments what you need, what’s resonating, what’s coming up for you. Why am I not surprised that I’m writing this with a migraine? All mistakes are my own (and sumatriptan’s).

Before I even begin, feel free to take a moment to reflect on how much pain has impacted your own writing life.

You might even make a note to journal a bit about later today. There’s a lot to dig into here. What has it kept you from? What has it given you creatively, in terms of material, connection to your characters, empathy? How has it forced you to slow down and pay more attention? What opportunities has it taken off the table? What adjustments have you had to make? How does it affect you emotionally? What about its impact on relationships? How has it impacted the way you navigate the world?

PSA:

I should say as a gentle word to those of you who do not have pain—please don’t email me or put in comments saying you hope I feel better. Here’s a great post by Sophie Strand on how to talk to friends with illnesses, chronic pain, and disability. It’s okay if you didn’t know this. Now you know! Onward.

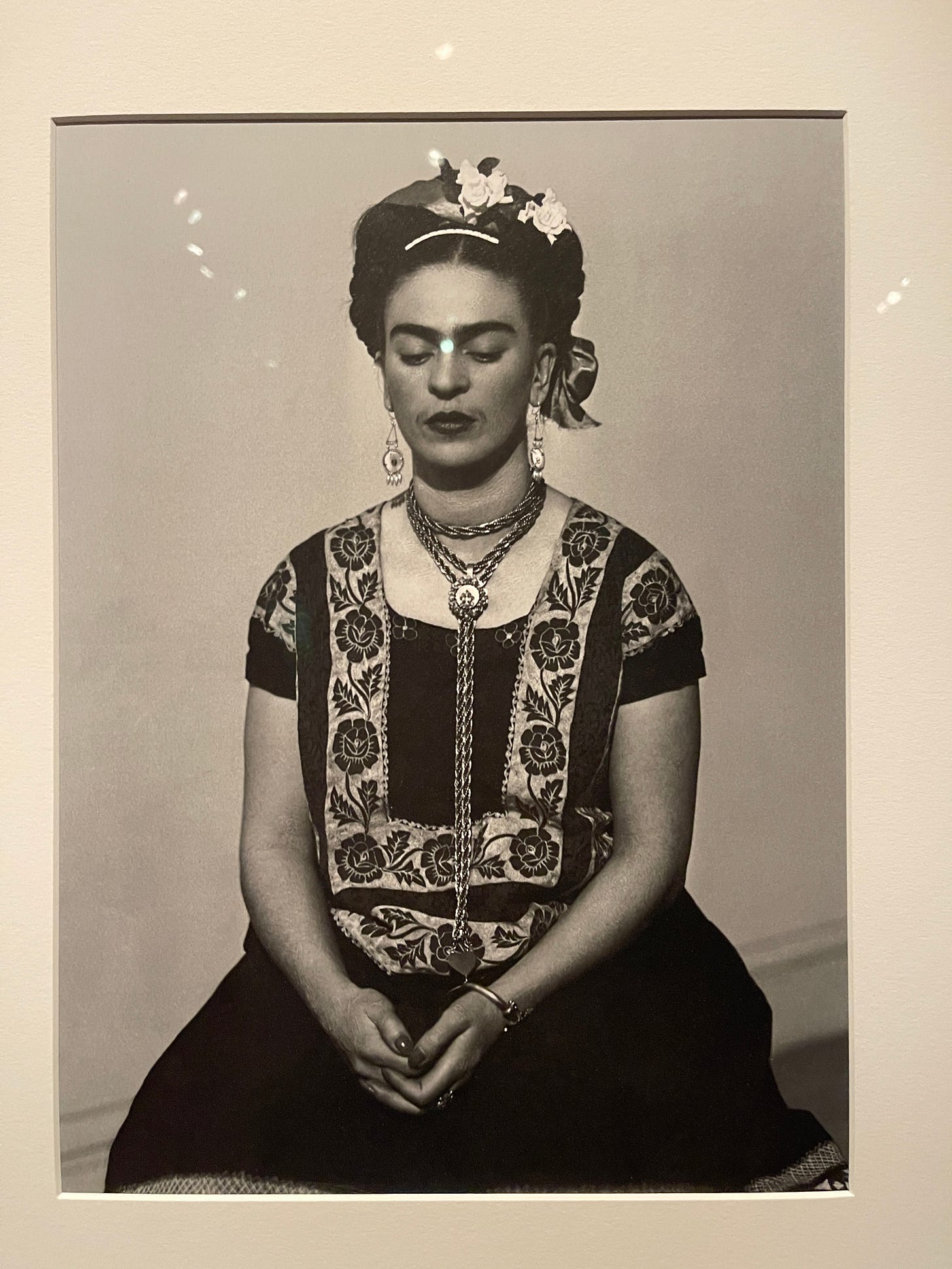

So many writers I know work through pain or have to spend a lot of time away from their work because of pain. For most of my adult life, I’ve loved Frida Kahlo in large part because she is one of the few women artists who have been so open about their physical pain. This summer, I visited my dear friend, Camille DeAngelis (is there a post I write that she doesn’t make an appearance in?!), in Richmond, VA, and there was a Frida exhibit at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts that included this photo of her by the French photographer Dora Maar.

It’s Frida in Paris in 1939. Unlike most of the images of Frida we see in photographs, she doesn’t appear confident here and defiant here. In the curator’s note, they mention her seeming insecure and uneasy. I don’t know that I agree with that. I think it’s a rare glimpse of Frida taking her armor off. We see the burden here of being in constant pain and it’s a quiet moment of her gathering her resources to go back out into Paris and be the Frida she’s expected to be, the Frida with the big laugh, middle fingers up.

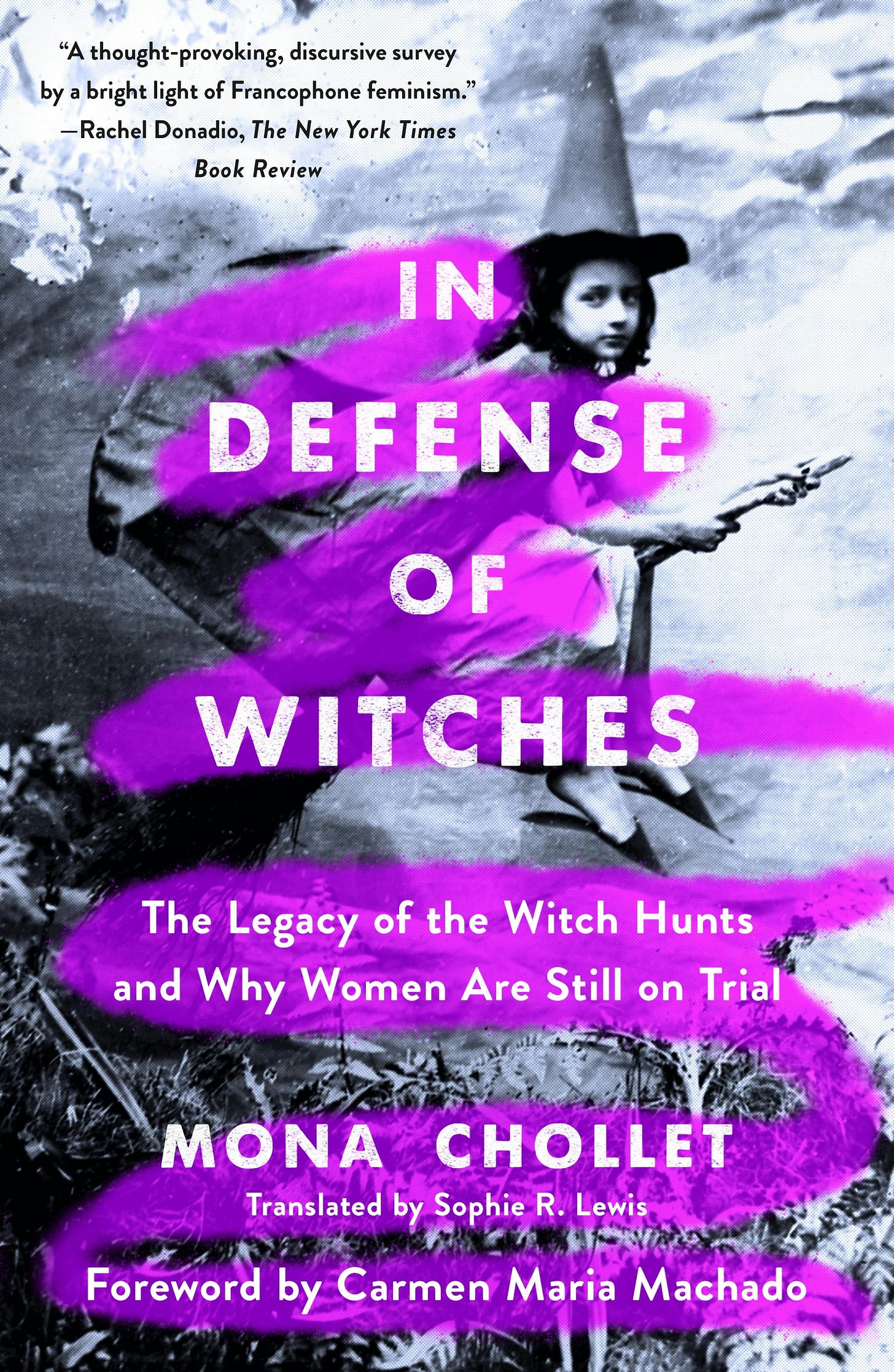

Many women—Sylvia Plath comes to mind—have been expressive about their emotional pain. This is territory that female artists seem to be allowed to freely roam in. It is no surprise, though, that a society that expects the female form to be corseted, covered, demure, would be uncomfortable with its female artists exploring pain in the body, as Frida did in her art. It can barely stand it when female artists dare to speak of pleasure—it certainly doesn’t want to hear about our pain. Just look at the etymology of the word “hysteria” to learn all about the history of women’s pain being dismissed by male doctors. A good seasonal, feminist read here would be Mona Chollet’s In Defense of Witches.

It is only recently that the reckoning with chronic pain, especially chronic pain in women, has begun.

It’s important to me that as writers we make space for one another to talk about this because I know it impacts so many of you on a daily basis. So many lost writing days, weeks, months, years.

So much money spent on supplements and treatments and doctors that don’t work. Loads of stress. Whole parts of your bandwidth and brain that are taken up by managing your health. It can be so hard to have space for your creativity. Please let me know in the comments what kind of topics you’d like me to dig into for you. I’ve got lots of resources I can share, tools to work with pain, and strategies for how you can keep writing or keep in touch with your writing amidst flares, depressive episodes, and more.

Today, I wanted to dip into something that’s come up in our writing world around how the story of pain is told, who gets to tell those stories, and what publishing allows through the gate. Curious what you all think…

Salty

If you’re not aware of the controversy surrounding the memoir The Salt Path and its subsequent books—yowza! In short, a story that many of us held as a beloved literal and metaphorical journey of triumph over adversity (poverty, illness, the failure of multiple systems) and the healing power of nature, the kindness of strangers, and how one’s beloved can get you through the worst of times turned out to be, in many ways, a sham. Its author, Raynor Winn, has been accused of theft, getting very creative with her telling of just how she and her husband Moth came to lose their home, and—the worst part—of very likely misrepresenting and—possibly outright lying—about her husband’s life-threatening illness. All of this was revealed in a jaw-dropping investigative report by The Observer, the kind of article I hope is never, ever written about me, but that my Slytherin heart would very much wish on my worst enemy. The literary world went wild, ink flying everywhere. We’ve all got opinions.

I bring this up because there was a wonderful piece in Lit Hub that my mother-in-law shared with me written by a British author, Polly Atkin, who viewed the whole fiasco through the lens of being a disabled writer. It was only after reading this piece that what Raynor did finally felt personal to me. Before, I felt upset as a reader, and a human being. My trust had been broken because I had been genuinely rooting for her and Moth. I’d hurt for them, and rejoiced with them. It felt shitty that I’d been lied to. But when I read this piece by Polly Atkin, I began to see how Raynor had broken faith with her fellow writers. We don’t have a code per se, but there is an understanding that if we are writing memoir, we are telling the truth—the whole reason the genre exists is because its readers connect to the story being true and have an entirely different relationship to the authors as a result. Of course, with memoir, we give writers the benefit of the doubt that memory is notoriously unreliable, but we assume that the basic facts are true, like a diagnosis or the circumstances surrounding how one gained or lost their finances.

Raynor wrote a story claiming that she and her husband, who was presented as essentially dying of his illness, cured him through walking the UK’s version of the Pacific Crest Trail. It’s an incredible story and, for folks who are experiencing severe illness, presented the possibility that they, too, might go on such a journey.

It occurs to me now, since this whole story is likely bullshit, how deeply harmful and dangerous her words are. How fucking cruel, in fact. For those of us who wake up every morning in pain, who have cleaned out our savings accounts because someone we trusted or know or a provider insisted that this is the cure or we need this test or these meds or this treatment. None of it works. Because the pain is chronic.

Because this is the body we have and there are non take-backs. And for the non-UK citizens who live in a neoliberal country that demands we pull ourselves up by the bootstraps, a country that has zero safety nets for medical care, it’s even more disheartening.

As a writer with chronic pain, invisible disability, and a complex PTSD diagnosis, I tend to write work that doesn’t have a happy ending. Things aren’t wrapped up in a nice bow because that is not my experience of life. It’s…complex. As it is for many, many readers, who long to see their experience reflected, for once, in the work they read. In her piece, Atkin chronicles an experience she had in a publishing mentorship with Penguin around the time The Salt Path first published where she was told to make her memoir about nature and chronic pain more uplifting. At the time, raves were coming in about The Salt Path. How inspiring it was. Heartwarming. Now we know it was a lie. Which drives the knife in deeper. Not only were real stories being rejected, but real stories about real pain were being rejected because this untrue story was creating a false narrative that was more commercially successful.

Atkin writes:

Nature writing only wants to admit illness into its pages if it is to show nature performing a miraculous cure.

There is a place for miracles—in our fantasy lit, for sure. As a reader, I reach for books like that when I want to be in a space where everything works out, where the bad guys are vanquished, where there is a potion that cures all ills. We need those kinds of books. But we also need spaces where we can see our personal experiences reflected with unflinching honesty. Where writers are fearless, where they tell it like it is, where they comfortable with uncertainty.

Atkin went on to write:

I was pressured to change the book to make it “less bitter” about illness. I was told repeatedly that it was simply not commercially viable to write a book about illness and nature in which I did not get better because of the nature. Without a redemptive Nature Cure arc, my work was deemed pointless, unsaleable. To not get better, it was clear, was both uncommercial, and uninteresting to readers. Possibly actively repulsive.

That word “repulsive” really stuck out to me, because it seemed to be a callback to so much of the narrative I’ve encountered as I’ve traveled the history of the oppression of women and their bodies as they’ve sought care throughout history. Male doctors repulsed by the female body, diagnosing hysteria, laziness, and all manner of emotional overreaction to real pain. If you’re a woman of color, you’re even more likely to not be listened to, disregarded, and shunned.

The word “redemptive” also stuck out to me. As writers, there’s this onus on us to make everything redemptive, but we are not in redemptive times. One of the things I appreciate so much about my Zen practice is simply being with things as they are. There is no need to make a thing redeeming. It just is. I have this body. It just is. Yes, I can see how it has made me more resilient, yet that resilience has also brought about coping strategies that aren’t necessarily healthy. So my silver linings are sharp. It’s that Frida photo. Heavy. I don’t want to read a story about how someone got cured because I’m not cured and I won’t be. I have a body that, as my doctor says, is very sensitive to the viruses it has contracted. It will always flare up and it’s a matter of managing those flare-ups. How comforting would it be to read a story where someone else also shared how they walk this path and find pockets of joy despite the pain?

The path I walk is salty, too. I’m a California girl of Greek and Celtic descent. The sea has always brought me back to myself, aligned me with Source. It does my soul good. And that can actually be enough. But it is not a miracle cure. Raynor Winn, who is a gifted writer and storyteller, could have told that story, of how the sea and the wild spaces alongside it, is good medicine. It wasn’t what she chose to do, and because of that, she has caused great harm. The sliver of hope here is that the lack of fact-checking on her publisher’s part has unmasked publishing’s complicity in silencing voices of the disabled and unwell. This is good. This is important, especially now. In my recent post, “A Matter of Words,” I discussed how the current administration’s actions against artist’s at the Kennedy Center and at museums like the Smithsonian are disturbingly similar to that of the Third Reich’s policies toward artists they considered “degenerate.” When publishing gate-keeps in a way that silences writers who are disabled and lifts up writers who go from disabled to abled, this supports a culture that, again, harkens back to Third Reich policies. As early as 1939, the Nazis began killing disabled children and adults. Making these connections is not alarmist in the least. We are seeing how fast things in our society can change when people without empathy or regard for the dignity of all people are put in power.

It’s imperative that we, as writers, demand that our publishers are not complicit in any kind of gate-keeping that promotes the silencing of narratives that don’t meet the capitalist criteria, which is often ableist at its core. If you don’t feel well, you’re not a happy consumer, now are you?

I recently finished John Green’s Everything Is Tuberculosis, and he had this lovely reflection on how writing is like a game of Marco, Polo. He says:

“I think of writing as sitting in my basement for years saying ‘Marco, Marco, Marco.’ And eventually, the book comes out, and for the first time, I hear someone say ‘Polo’ back to me. It’s the loveliest thing. It’s the most amazing thing. And it’s true for all creative work.”

Here I am, saying Marco. I’m listening. Polo? Anyone?

Yours in doing right by the miracle,

Two things that resonate for me (well, most of this does), is "Hope you feel better" and the pressure to write "less bitter". Sometimes, one just isn't going to feel better, and that has been made clear to me more than ever as Joe goes through this terrible experience of cancer. People tend to say whatever it is that makes themselves feel better, so I get it, but the "You've got this" comments drive me insane sometimes. And in the same vein, when I write about my side of this experience I feel responsible to make sure everyone else is feeling okay, positive, or uplifted regardless of how I feel or what is going on. However, I have learned to not give in to that pressure so now I sometimes feel afraid I'm being too much of a downer. But I am a realist through and through, there is no taking it out of me or my writing. I want to face, feel, and write about what is actually happening not what I wish was happening. And slightly tangential, but not entirely, did you happen to read Liz Gilbert's piece about her new book in the Guardian recently? Because I'd love to talk about that with you and I'd like to punch her in the face. (But I also still love her. It's complicated.)

Thank you for opening this up for all to read. I’ve lived with chronic pain for most of my life and more severely over the last several years. There is no cure for what I have. I’ve tried expensive treatments, risky infusions, and all manner of vitamins. I never read the memoir in question as I find it hard to read things with such happy endings because like you expressed, that is not the case for most, and certainly not for me.

So many things about this are frustrating because yeah I spent years screaming into the voice (medical professionals) about my pain and suffering to be answered back with shrugs, or exercise more or lose more weight, or eat less of things I’m already not eating. I’m a 40 yo black woman with three kids so clearly all those things explain it over an actual diagnosis which took 6 years before anyone took me seriously. The utter disregard of the author but especially the publisher is what has caused so many people to lose respect for publishers, authors, and books in general.

This isn’t the first time a memoirist has been ousted as a fabricator or elongated truth teller. It can make people question the validity of memoirs and the essence of true. Something many of us with chronic pain can already relate to.